View Camera – Gilles Larrain: The French Chef of Photography

Miles Davis, View Camera cover, 1997

Miles Davis, View Camera cover, 1997

PHOTOGRAPHER GILLES LARRAIN is busy making “soup.” Though he is reportedly a gourmet chef, he is making this soup in the darkroom, using his own recipes and mixing things together so he won’t have to use commercial chemistry.

“It is time consuming and impractical,” he says, “and if you want to make money you must never do that. You can just press a button and that is it, then press another button and send it quick. I work in my darkroom because I enjoy it and because I want my life to be something I am happy with. I come from an old family where money was never that important and I feel completely out of touch with a world where money is the only thing that counts. I am not a money maker… my world is my pleasure.”

In case you haven’t guessed, Gilles Larrain is French, very French. Reluctant – and I don’t blame him – to lose the charm of his European dialect, he requires close attention. It is easy though to be attentive to Larrain because his persona and his surroundings are unique, as is his photography. It is extremely traditional, extremely beautiful; the uniqueness lies in the perception.

Jane Seymour “Exquisite Creatures“, 1985

Jane Seymour “Exquisite Creatures“, 1985

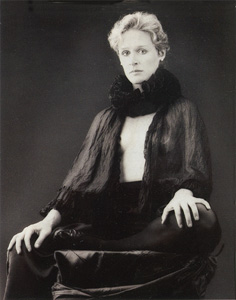

Glenn Close “Exquisite Creatures“, 1985

Glenn Close “Exquisite Creatures“, 1985

Miles Davis, Night Music

Miles Davis, Night Music

A large portfolio, for instance, holds portraits of gallery owner Leo Castelli, writer Norman Mailer, Talking Heads member David Byrne, Mikhail Baryshnikov Miles Davis, an endless homage to what Larrain refers to as the landscape of the soul. In one, actress Glenn Close sits like a Buddha, her hands on her knees. Her position is vulnerable and she is almost topless, unprotected by clothing, wearing only a light chemise. It is a sensual portrait. “She is almost transparent,” says Larrain. The portrait is from the book “Exquisite Creatures“, that he did with Robert Mapplethorpe, Deborah Turbeville and Roy Volkman. For the magnificent collection of figures from the American Ballet Theater, Larrain painted his own backgrounds. “I was looking for a Valesquez lighting in these pictures,” he says, “see the way the costumes are… very eighteenth century romantic… not too much chiaroscuro – less dramatic. It’s a light that doesn’t provoke high contrast but modulates the face in a gentle way without describing every facet…a poetical light.”

The setting where much of Larrain’s work takes place is his two level studio on the first floor of a six story building which he owns in the heart of New York’s Soho. The space is wonderful, the walls filled with Larrain’s photographs. In the front room is a small collection of African sculptures, formerly owned by the French poet Appolinaire, which his father, a collector, had purchased in a Paris auction. A group of family portraits, his aunt, cousins, and mother, were taken by Man Ray in 1932. On another table a Renaissance lute sits majestically, contrasting with a motorbike parked at the front door.

On the wall is a towering portrait of Miles Davis which Larrain and his wife Coco, a painter, worked on together, combining the original photograph with oil painting. It is powerful, Davis posing with his trumpet.

Larrain did many portraits of Miles Davis who first came to the studio when Columbia Records sent him to have a cover done for his record album, Decoy. “He was independent,” says Larrain, “and I knew he was to be very difficult. ‘I’ll give you five minutes,’ he announced. I asked him if he was thirsty and he answered, ‘I’m always thirsty.’ So we had some delicious Spanish wine and I put on an old flamenco tape and he asked me why I played such music. I told him it is because I play the guitar. He said, ‘Go get your guitar.’ I said, ‘Go get your trumpet.’ We played a little music, had a little wine and some wonderful prosciutto and we connected.”

Bob Lafosse & Leslie Brown, 1985

Bob Lafosse & Leslie Brown, 1985

On the lower level of the studio the strobes have been left on and pop intermittently. In an adjoining room a long dining table is set beneath a huge print of dancers Leslie Brown and Bob Lafosse, photographed for the American Ballet Company brochure. Everything in the picture is static but the backdrop, a long, flowing blue cape which rests above the dancers, the movement of the garment symbolizing the motion of dance. Larrain explains how small lead weights had been attached to the bottom of the cape and while he readied to shoot, two assistants, one on each side of the dancers, threw the cape in the air. Larrain photographed. He described the effort, “not too high, not too low – ah – I’ve got it.”

Many of the ballet photographs were done using Polaroid 665 black and white film with a camera back that fits onto his 4×5 Sinar. There is a negative attached to the image which is good quality and can be processed in the darkroom and washed in his own “soup.” His darkroom work is complicated which accounts for the strange and beautiful tonalities of his prints. Often the process involves exposing a black and white photograph for a long period of time in a fixer. Larrain explains that leaving a print for two days in a fixer tends to change the ratio of the blacks, and accidental things happen such as turning the image into sepias and metallic grays by changing the nature of the paper. The print must then go into the perma wash for hours to remove any trace of the IPO fixer.

Not only are Larrain’s alchemy and darkroom procedures his own, but he creates his own backdrops and even his lights. Using a series of honey-combs he can concentrate the light on particular area, diffusing or pinpointing it as if through a funnel. He may draw or sculpt as he wishes, keeping the light very soft. It’s a flash system that has a special nose with the various honeycombs focusing the light in the selected locations with no dispersion. We must conclude that Larrain is always in charge from the concept to the final production, which, by the way, often includes the framework that is often quite elaborate. His world is under one roof. Indeed it is. He and his wife, Coco, have been together since 1985 and live above the studio. His ex-wife lives on another floor and his daughter, now in Paris, maintains her own quarters on yet another level. Somewhere in the midst of all this are the tons of contact sheets, photographs and books that represent his career since 1968.

Larrain first came to the United States in 1955. His father, a diplomat, was Chilean and his mother French. Gilles was born in Dalat, Indo China. When his parents left America for Argentina, he went to study in Paris and returned later to attend New York University.

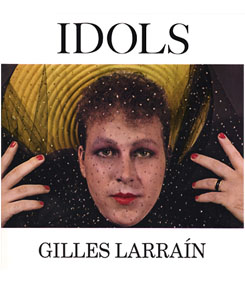

Lotta Love, Idols cover, 1972

Lotta Love, Idols cover, 1972

Between 1970 and 1973 he photographed the Coquettes, a group of transvestites from a theater group at Max’s Kansas City, the famous restaurant that was a very hot inner sanctum for artists, on Park Avenue in New York. In 1972, the book. Idols, edited by noted photographer Ralph Gibson, was published with the photographs of Harvey Fierstein, the writer Beauregarde, Tinkerbell and Taylor Meade, the poet friend of Andy Warhol. The cover reads, “These arresting photographs may delight you. Perhaps they will offend you. They will almost certainly inspire you to ask questions about yourself and your sexuality. They will not leave you cold.” The book is now out of print but an English publisher is seeking to document transvestites from the past and has asked to reproduce four of Larrain’s images in his book.

“I spent two weeks,” Larrain recalls, “correcting the color and fighting about cropping my photos. In one of Salvador Dali’s models, they cut too many millimeters off the top of his head. Why did they do that? Everything from the neck to the top of the head was conceived and photographed as a perfect curve and by cropping, they had disturbed the line. People have no sensitivity! Blindness!” Curiosity plays a major role in Larrain’s photography. For him taking photographs is about asking questions and he admits that he often takes a picture to see what it is about an image that has triggered his curiosity. Beauty beckons him as does mood and the way his memory works. “I was born in the Orient, and I remember the first time I went to work for the Club Med and the smell and humidity of the place I was photographing. The climatic presence triggered memories in me that went back to when I was three years old. There is such a complex web of connections and emotions.”

The complexity in his own work has grown accordingly. in a series of landscapes that he is presently working on, gardens and parks contrast. Urban sites in New York and Paris unite within one frame. He has sold thirty diptychs (sixty black and white prints) to a bank in Paris and they are soon to be housed in a museum. One photograph portrays the chaos and energy of Central Park and contrasts with a peaceful park view in Paris. “The images,” Larrain says, “somehow feed back and relate to each other, but there is always the difference. Difference is the theme of another concurrent series called “Twins,” showing two photographs of one person in the same position. One is clothed, the other, undressed. What happens,” he notes, “is that you can never duplicate the exact position. If the model moves away and comes back, something changes. The moment is unique. You can never reproduce it. I photograph two views of the same person and when they are nude and more exposed they have a different attitude. Very often the face is more relaxed when the model is unclothed. It’s very strange.”

In 1991, Larrain had a show at the Meadows Museum in Dallas, Texas. The pieces were large, one-of-a-kind prints transformed by dyes and coloring. He photographed a row of dancers and worked on each image separately in the darkroom, manipulating, toning, coloring and destroying parts of the picture by using acids and reducers until he got the print he wanted. Another series of what Larrain refers to as his photo icons is achieved in the same way. Photographs of Rossellini, Dali, John Lennon, architect Philip Johnson, museum director Tom Messer, Christie Brinkley and Billy Joel, as well as Laurie Anderson, Miles Davis and Robert Mapplethorpe, work in tandem and are related through the tonalities in this surprisingly cohesive and thoughtful work. These large images are comprised of individual photographs archivally mounted on stretched canvas. The backgrounds are then painted, often incorporating gold leaf in the finish. A final coating of encaustic acts to preserve the work.

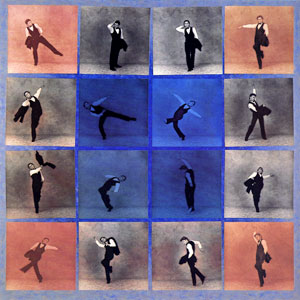

Continuum, Mikhail Baryshnikov

Continuum, Mikhail Baryshnikov

“When I do a series, it is a long elimination work before I get everything working together. Baryshnikov wanted a portrait of himself and didn’t want to be photographed dancing. I had him imitate the motions of how he would direct some choreography and create steps for his dancers. This was in 1982 when he was the creative director of the American Ballet Theater.” Jacket in hand, Baryshnikov made a few movements, dropped the jacket, then became more and more involved. He was dancing. Larrain put the images, toned with blues, sepias and grays, together. It was an entire process which he mounted in a way that tells a story about that moment.

Once again we see Miles Davis, this time in the format of a totem. The first image is a glimpse of his forehead and eyes, then the features unfolding in eleven segments. The final picture, taken just before he died, shows a part of his eyes and moves to just below his shoulders, the partial head against the background forming a veritable cross. The colors change as each segment evolves, going from brown to lead grey, every one unique. The variation is meant to record the moods of Davis, his musicality and sounds.

Leaves of Hypnos

Leaves of Hypnos

Some of Larrain’s most moving images were taken at Biscaya, an old castle in Florida. Originally owned by a French-American architect who brought ancient Roman and Greek sculptures there to glorify his gardens, it is currently owned by John Deere. The sculptures, made of very soft marble, now eroded by wind and sand, remain in situ within a jungle-like background. “These photographs are about change and memories obliterated and lost, things from the past,” Larrain says. “I used my own destruction of time, interpreting with lines of ink, and my final piece is no longer a photograph—it is an ink drawing.”

Artist, photographer, flamenco guitarist, Larrain lives a multiple life. He also teaches and last summer gave a workshop, The Art of Portrait Photography at his studio for the International Center of Photography in New York. “I have a place in France, too,” he says, “near Bergerac, like in Cyrano. It’s a farmhouse and in the near future we will be doing workshops there. ICP wants to run two week programs in France. I will even teach cooking there because the region is known for its food, mushrooms and truffles. It’s also near Bordeaux, in the wine region.”

Larrain has been a lucky man. “I have never worked for anybody,” he says. “My life has been really blessed and making photographs is a passion. The day I go into my darkroom and am bored with it, I will open a restaurant. I love to cook.”

BY ROSALIND SMITH, 1997