Zoom Magazine, English Edition 1981

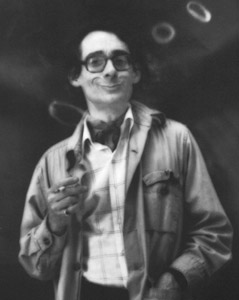

Maurice Girodias, 1979

Maurice Girodias, 1979

If you know the name of Gilles Larrain, this portfolio of pictures will surprise you. This is Larrain the artist – whose materials are air, smoke, light, water, neon tubes – Larrain the sculptor of the environment. And this is Larrain the photographer – whose subjects were New York transvestites with impossibly painted faces, and young men with firm flesh bulging through their tight leather outfits – Larrain the documentor of the sexual underworld. (See Zoom 16 French edition, or his book, Idols.)

Thus, after so many years travelling in the opposite direction, Larrain rearrives at the social portrait, but from the opposite direction…

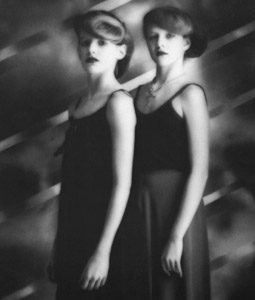

Where the pictures of transvestites were dramatic and brightly coloured, these new portraits are soft and black and white. The sitters, instead of being transfixed and laid bare by the lighting, are now caressed by it. The approach, instead of being agressive, in some ways brutal, is gentle and caring.

Mali , 1978

Mali , 1978

The subjects respond differently, too. When Idols was published, Larrain remembers, they were very nasty, and some were threatening to sue me, or shoot me. The subjects of these portraits, by contrast, are flattering, he says. So far it’s been like a love relationship with these people. But that will die too, and something else will emerge… What he is after is what he describes as the landscape of the soul, while apologising for the fact that it sounds a little like a slogan. On the sessions, he adds, I feel like I’m a shrink, a psychiatrist, because they come to me for an answer to their image. Remember, they are not models. They are not used to being photographed- the idea frightens them!

The portraits are taken at Larrain’s studio on Grand Street, in New York. Actually it is not particularly grand, it’s in the Soho area. From the outside the buildings look like warehouses. The huge studio space on the ground floor seems more like a workshop, with its scaffolding, tripods and banks of lights. Standing there, as a visitor, does not make one feel comfortable, let alone chic and sophisticated, though many of Larrain’s subjects are.

The Two Sisters, 1980

The Two Sisters, 1980

That’s why it’s important to do them in the studio, he explains. I see people at parties, being very smart, or very aggressive, or very protective – being an exciting man or woman. If they are In their own environment they are very assured – they are comfortable in their own habits, in their favorite chairs, and so on. Then they come to the studio ‘ This is a foreign land for them, a foreign language. The ups and downs of their reactions are amazing, as they try to find their identity in these surroundings. I find that fascinating. That’s what I try to capture in my photos… The beginning of a studio session is always very slow, very tense. I often touch their hands and find they are wet with perspiration – they are afraid. It’s not that I am being sadistic. or have power over them, it’s just that the situation is awkward for them.

Not being a fashion photographer, I don’t cast or direct my subjects, but I’m very careful to leave an area of freedom around them. They are already imprisoned by the lighting, by the elements of the studio. So I try to move about very quietly, and by not speaking too much, keep a kind of silence of meditation. Sometimes with a woman it borders on eroticism – it’s a very ambiguous relationship, actually. I don’t know how I do it myself, it’s not a formula. When it works, I know it works. When the session goes well it creates a balance, a harmony. I know I’ve got something, and then I stop.

Jaime Olé and Carla, 1980

Jaime Olé and Carla, 1980

It is interesting to play the psychologist for a moment. It seems possible that the desire to fix an image, permanently, in a photograph is a reaction to the impermanence of Larrain’s childhood. This is borne out by his first choice of profession, which was not photography but architecture – an even more egotistical pursuit. An even more romantic profession. Larrain trained at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts and worked in City Planning in Paris. He found the reality was different…

In the 60’s, it was still possible to think of building forever – to hold the idea that constructing the world, the eternal city, was a cumulative process, ending in perfection. Now we can see that the city is in a permanent state of decay – continually crumbling, and continually being renewed. But simultaneously we have discovered that the photograph is permanent, not transitory, not created only to fade. After all, far more photographs survive than the buildings they record.

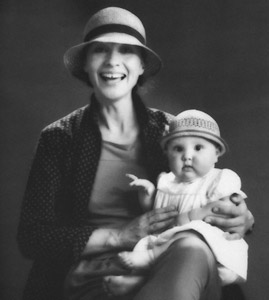

This gives the photographer a new dignity, but also a new responsability. It is no longer enough to record the surface appearances, whether of buildings or the painted faces of the punks in Idols. Now the challenge must be to penetrate beneath the surface to capture the quintessential character of his subjects: For the portraitist, that means capturing the landscape of the soul.

Of course this is a romantic notion, and these are romantic pictures. Like the Idols pictures in their own day, these portraits capture the romantic aura of the present. Well, that’s the way I am, laughs Gilles Larrain. I do things without goals. I go out and tilt at windmills. I am a Don Quixote!

François Dallegret, 1977

François Dallegret, 1977

The Madona of Toronto, 1978

The Madona of Toronto, 1978

Well, which of us is not envious of him! The interview is over, Larrain and I leave the studio and walk down to a Chinese restaurant nearby. Enjoyable pictures, enjoyable conversation, enjoyable food. After the meal we open our Fortune Cookies. Mine says Keep your eyes open before marriage, half shut afterwards. And Gilles Larrain’s ? We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give, That just about sums it up.

Jack Schofield, 1981